“What will the future bring? From time immemorial this question has occupied men’s minds, though not always to the same degree. It is chiefly in times of physical, emotional, economic and spiritual distress that men’s eyes turn with anxious hope towards the future, and when anticipations, utopias and apocalyptic visions multiply”

Carl Jung’s words may have been written at a time long before anyone had even began to think about Coronavirus but they came from experience. The famous Psychiatrist lived through both World Wars. His experience in living through a crisis was second to very few people alive today.

When the present is so difficult, as human beings, we have to spend a portion of the time looking to the future, whether in preparation, optimism or despair.With such uncertainty surrounding day to day life, the schools of thought of what the future will look like varies hugely.

Scholars and experts from within the property profession are publishing their own predictions, throwing out percentage increases or reductions and other thoughts on the utopia or apocalypse that could await us. This article will not seek to trumpet or chastise any particular commentator or their predictions. There is no crystal ball. There is no one size fits all approach. This article is aimed at informing readers of the various considerations so people can determine their own opinions, supported of course by their own knowledge.

This is not purely about house prices. It is also about the changing demands that as a society we may place on our housing.

What does history teach us?

The property market, in its various forms and ‘guises is of course cyclical. Every so many years, there are macro or micro economic factors which affect how we as states, individuals or groups of people, behave.

House prices nationally today are around 8x average earnings. All the way back in the mid 19th century, they were 13x average earnings. Only the rich owned their own homes.

We then had decades of that multiplier falling as the Victorians and Edwardians went on a building spree and the average house became smaller and smaller. The average house plot size fell from 913sqm to 268sqm in the second half the century and was to fall much further as time went on, whilst the average price fell by around 23% in the same time.

The country adapted to it’s new requirements. Poorer people needed to be housed, often close to the factories and plants they worked in.

After World War 2, the Government recognised again that the lower skilled workers were at the top of the list for new housing provision. After the private sector building boom of the 1930s and the pause and recovery during the war, came a public sector building boom that would last through the 1950s-1970s.

In the 1950s and early – mid 1960s, this building boom was largely of streets of public sector housing, much of it traditional red brick terraced and semi detached. By the late 1960s, the competing political colours were auctioning election commitments on the number of homes to be built. Housing returned to the top of the political agenda. To meet with some outlandish commitments, local authorities were tasked with building the homes Government set them targets to and often turned to non traditional construction methods such as Wimpy No Fines and Large Panel system build.

For anyone who hasn’t seen it, I would highly recommend the documentary ‘The Great British Housing Disaster’ (link below) which can be found on youtube and illustrates the scandalous practices which epitomised this time of building non traditional build properties.

Will Coronavirus change our housing needs?

Undoubtedly so, yes. The extent though depends on a number of factors.

- Inequalities of lock down

- How long the virus lasts for

- Cramped living conditions and HMOs

- Death, divorce and debt

Inequalities of lock-down

When Boris Johnson caught Coronavirus, the daily government briefings repeatedly used the line that the virus does not discriminate. There may be some truth in that but the effect of the virus on the communities it hits certainly does discriminate.

As I type this article from the relative luxury of my home office in the knowledge that I have room to breathe and gain solitude within the house if needed, I am conscious as we all should be that there are many who are less fortunate.

The BBC’s Emily Maitless reported on it well as she extolled that Coronavirus is not a great leveller if you’re working class.

How long the virus lasts for

When the country does recover from the virus, as it undoubtedly eventually will, the section of society that calls small cramped living conditions home will come to reassess whether they can continue living in such small spaces.

The longer we are on lock-down, confined to the same four walls for extended periods of the day continues, the more dislike for those walls will grow for some.

The type and size of the housing we as a society demand may change. Outside space could attract a premium. Developers with large numbers of unsold small apartments may struggle to sell them.

Those who buy high value small apartments in central London may decide that more space and external space further away from the bright lights and crowded tubes is more attractive than they previously thought. The longer the virus maintains us in lock-down, the more those people will learn to live without the cafe culture that may have initially attracted them to the purchase. The short commutes into central London may become less valuable if the newfound appreciation of technological ways of working at home becomes the new norm.

In places like London, which many argue is already overpriced, there may be a shift outwards and into larger properties. Developers would be wise to take heed as the demand could change.

Cramped living conditions and HMOs

In recent years, there has been a movement away from allowing HMOs. Multiple Article 4 directions have been used to remove the permitted development rights that allowed HMOs to be created.

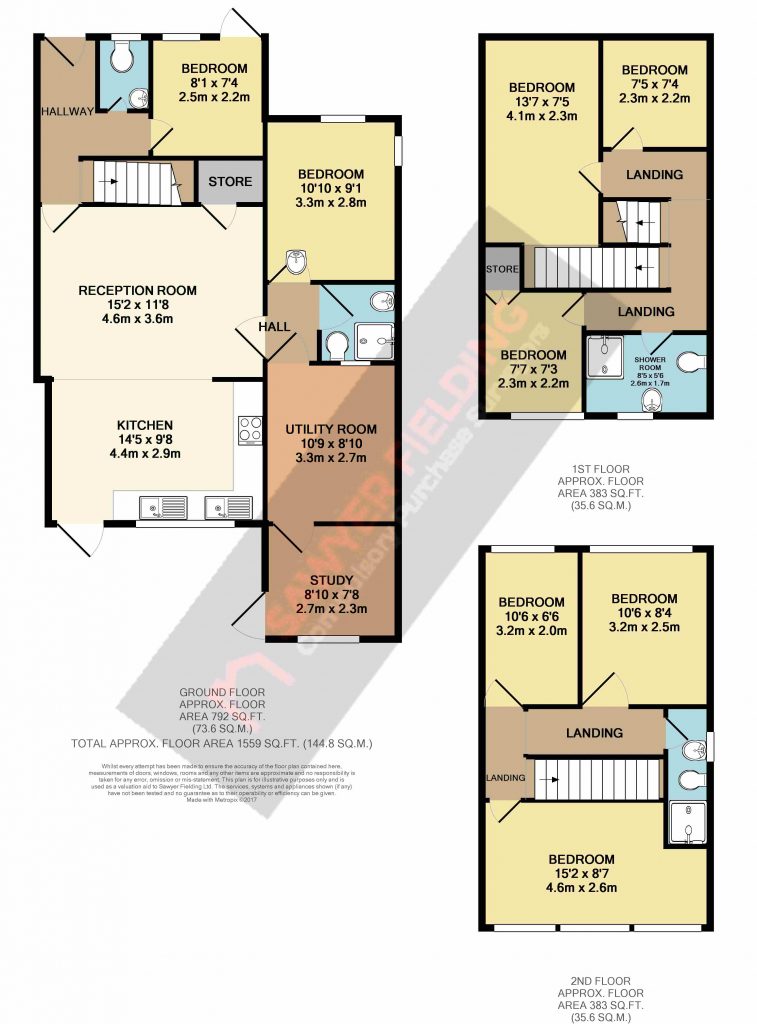

The floorplan below is from a property which our parent company valued, a three storey house being used as an eight bedroom HMO.

Those living in HMOs will find lock-down more challenging than most. Whilst sections of the public have often turned a blind eye towards some of the worst practices of overcrowding (admittedly there are many HMOs and student houses which operate perfectly well), the impact of the virus will shine a light on these practices.

Landlords who operate dubious letting policies are likely to be an easy target for Government when life returns to normal and tax receipts need to increase.

Perhaps the worst we as Chartered Surveyors have seen was a 2 bedroom flat where eleven people slept on the living room floor and a number of others in each bedroom.

That may be closely rivalled though by one 2 bedroom late Victorian house designed with two bedrooms. Both reception rooms were being used as bedrooms. One of the actual bedrooms on the first floor had been split into two, both below minimum Housing Act sizes, the loft had been boarded with a bed up there accessed by stepladders, with no window and at the rear, a single storey wooden extension without utilities housed another bedroom. Our client tried unsuccessfully to convince us to value it as 7 bedroom house.

Practices like these have historically not been clamped down on as much as many would like to see them. Times may change.

Death, divorce and debt

Much has been said of a rather morbid nature that the more deaths there are, the more property prices will fall and that it will have a profound impact. I disagree.

Certainly, there will be a larger number than normal of sales where the owner or owners have died. However, even on a reasonably worst case scenario from where we are now, two and a half weeks into lock-down, the numbers of additional properties that could come onto the market in the coming months due to death, is such a small percentage of those expected to come on, I can’t see it making much of a difference. It may also be staggered over many months as well as families decide whether to sell or keep. Increasingly lengthy probate processes may delay sales coming to the market as well.

Coping with life under lock-down is challenging for the best of us. When many of us got married, we committed to our partners ’til death do us part’. There was nothing in the marriage vows that I remember about 24-7 for weeks or months on end.

Sadly one profession that will do well out of Coronavirus will be divorce lawyers. The anxiety of dealing with the threat of the virus in a confined space with little external support will drive many couples apart. Some marriages will be strengthened by inner resolve but many will buckle under pressure.

This will in turn create new households. Whether this additional demand is enough to impact on the market in any noticeable way depends on a number of issues such as how long the lock-down is for and whether government restrictions become more draconian or not.

What is perhaps of far more relevance is the level of debt that individuals carry through to the other side of the crisis. The level of national debt shall be discussed later.

As I type this, I am thinking of two particular friends, one who financially is doing very well from the virus and another who is loading himself up with debt. Both of course, like many others, are faced with a number of challenges such as homeschooling children and having movement restricted.

One is a teacher on full pay whilst only having to work one day a week as the school he works at have a rota of which teachers are required, with a limited number of children to teach. His expenses are down but his income is stable. The other is a fellow Chartered Surveyor who has been furloughed, under threat of otherwise being dismissed. Whilst many can reign in expenditure to the point where they can survive on the governments job retention scheme cap, others like my friend have committed outgoings that are larger. His only solutions are increased debt or using savings

If there are more people like my second friend than the first, ability to buy elsewhere will be hit, reducing demand. When demand falls, so do prices.

Mortgage lenders attitude towards borrowers with increased debt will be critical. If the computer says no, based on unchanged parameters, there will be less borrowing. Less borrowing means falling house prices.

Some mortgage lenders will also be wary about whether applicants are furloughed because companies genuinely want to keep them on or whether it is simply a means to secure an income. As we come out of this crisis, many companies may consider that they can cope perfectly well with a smaller core team. Furloughed staff may soon become unemployed people. How mortgage lenders approach the threat of knowing which category applicants fall into will be interesting.

Who does Government want to help?

When we come out on the other side of this virus, as we will soon (I keep telling myself in hopefullness), the Government will have some key decisions to make.

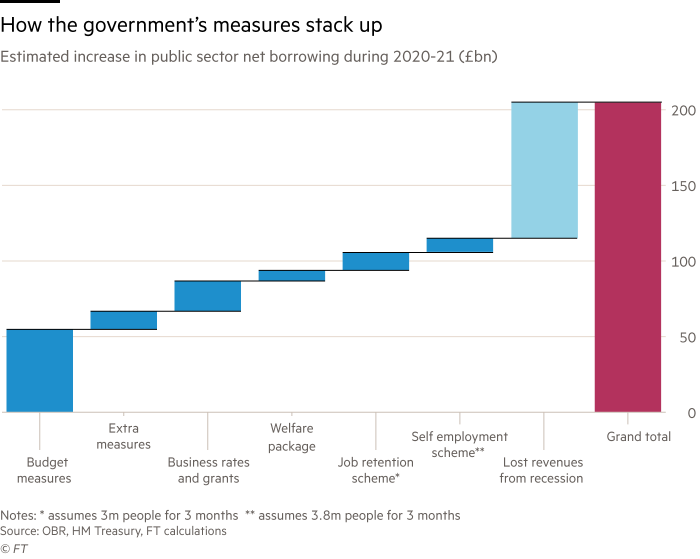

The longer the crisis lasts, the more damaged the economy is likely to be. When the Conservatives won a healthy majority in December at the General election, it did so partly on the back of a series of significant spending commitments that many said the country couldn’t afford. The cost of measures put into place to combat Coronavirus has significantly increased this.

Looking the above HM Treasury table, the lost revenues from a recession is the most challenging loss of all. As this is based on a 3 month estimate, if the virus takes longer to recover from, the challenge will only be greater.

When life does return to normal, Government debt will be huge. Austerity mark 2 may be just round the corner. In my experience, sequels are rarely as good as the originals.

That debt will need to repaid as the PSBR is reduced over time. During Austerity 1, the public sector workers took much of the hit as the Government had greater control over their wages. Public sector workers won’t be the soft target they previously were due to significantly increased public sympathy and respect for many of them. The NHS perhaps earning the greatest plaudits.

Government will need to consider who it wants to help. If wages in the lower skilled (or certainly lower paid) jobs increase, this may help support the first time buyer market. If the politicians have a short memory, the public sector may once again find itself the target.

Many are calling for a stamp duty holiday to stimulate the housing market. We are a nation of property owners, with our view of house prices often mirroring our attitudes to vital consumer spending. Such a tax give-away when the public purse is running on empty is unlikely but perhaps more minor reform to act as a stimulus could be provided.

I suspect that the Governments Help to Buy scheme will be extended further and potentially reviewed to help public sector workers even more. A new ‘homes for heroes’ soundbite for the government espousing the new type of heroes would be politically popular, especially as the Conservatives try to shore up support from those who lended their votes in the last election.

What will happen to house prices?

The largest picture and the shortest section of this article.

We are unlikely to know for quite some time. Land Registry data will be based on an incredibly small number of sales for the next few weeks or months. The sample size is likely to be too small to provide any accurate reflections.

It may be that the market crashes, it may be that there is little impact. We probably won’t know until months after life returns to normal when accurate data starts to come through.

We can look at the market crash of 2007-8 for guidance but it’s not the same. Demand fell far more than supply at the time. For a period of time, government restrictions will artificially reduce both. We won’t know where they stand until some time after restrictions are lifted.

I don’t know what will happen. What do you think will?

10th April 2020, written by Dan Knowles MRICS, Director and RICS Registered Valuer